Presidential Drinking

Part 1: Washington to Jefferson

The story of Prohibition is very much the story of America’s relationship with alcohol throughout our history. It has shaped our politics, our culture, and our economy. Changing American tastes and values had enormous influence over just how present alcohol, and what types of it, has been in our society. A fascinating gauge of those changing tastes is looking at how our presidents from the Founding Fathers all the way up to the incumbent have interacted, or not interacted, with beer, wine and spirits.

In this series, Presidential Drinking, we’ve dug deep into what place alcohol had in each president’s life from their favorite drinks to whether it contributed to their business practices throughout their lives to whether they… well… imbibed a little too much from time to time.

President George Washington, served 1789 – 1797

What was his drink of choice?

How about everything? George drank as a soldier, as a general, and as a president. He’d down a bottle of Madeira, a favorite fortified wine of many of the Founding Fathers, at night. He might sip some rum or beer along with it. In general (pun intended?), Washington never met a drink he didn’t like, and he partook in some of the finest that Colonial America had to offer. He’s even rumored to have been served an early version of our legendary local libation, Chatham Artillery Punch, during his 1791 visit to Savannah. Another favorite spirit of Washington’s was Laird’s applejack brandy, one of the country’s oldest distilleries.

Was he in the booze business?

President Washington wasn’t just IN the booze business; he was one of the most prolific producers of whiskey in the country after his presidency. In a way, he was the booze business at the time. In the last year of his life, 1799, his distillery at Mount Vernon churned out an astounding 11,000 gallons of whiskey in that year alone. He had published beer recipes and generally knew what he was doing with all things fermented and distilled. For all his expertise in selling the stuff, he still put a tax on liquor revenue that led to the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, one of the first major tests of the strength of the brand-new U.S. Constitution. Even his political challenges were whiskey-soaked!

Did he party?

George wasn’t exactly a party animal himself, but he sure knew how to throw one. George and a couple dozen of his army buddies racked up more than $17,000 in modern money in alcohol expenditures while celebrating the signing of the Constitution in 1787. He even gave out intoxicating punches to encourage voting at the polls. No wonder he secured the presidency unanimously!

George Washington set an example of commitment to the Constitution, steadfast leadership, and patriotic duty that many presidents since have aimed to match. Even fewer have come close to his love of a glass or pint of something strong. Still, his vice president and successor was no teetotaler!

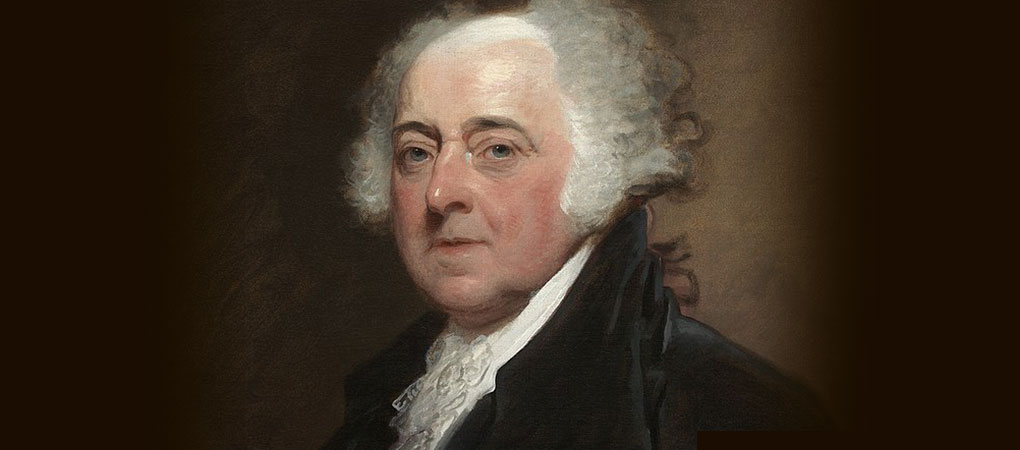

President John Adams, served 1797 – 1801

What was his drink of choice?

When reading about John Adams and alcohol, the first anecdote you’ll find is his daily morning cider. Some sources say he drank a whole jug of the stuff with his breakfast. Others say it was just a small glass. Regardless of the quantity, Adams liked the stuff enough that he wrote in letters about trying to develop his daily cider as a consistent habit. Basically, he treated hard cider like orange juice. He really loved the stuff!

In several letters to his friend and Harvard professor, Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse, the Founding Father was downright incensed that cider had fallen out of style at Harvard. He even blamed health problems among the students on their new affinity for wine and spirits, arguing that cider is “all the Liquor I can drink without inconvenience to my health.”

Cider aside, Adams also told Waterhouse that he’d tried wines from all over: France, Spain, and Germany. He drank Madeira, a favorite of Colonial Americans, before bed. Before he was George Washington’s vice president, he served as the first ambassador to the United Kingdom. He’d sampled, and enjoyed, different kinds of beer all over London. Adams didn’t limit himself; he tried everything that came across his path. It seems to have worked out for him. President Adams is one of our longest-lived presidents, dying at age 90 of natural causes.

Was he in the booze business?

No. Adams, a lawyer by trade, seems to have had others do the manufacturing for him. He preferred them to age his ciders AT LEAST one year, even going as far as two or three years. He also didn’t seem to know much about making alcohol as, even in times of desperation, he never sprung for making his own. While the Revolution was raging and Adams was called away from home, he complained in a letter to his wife and confidant, Abigail:

“I would give three guineas for a barrel of your cider. Not one drop of it to be had here for gold, and wine is not to be had under $68 per gallon… Rum is forty shillings a gallon… I would give a guinea for a barrel of your beer. A small beer here is wretchedly bad. In short, I am getting nothing that I can drink, and I believe I shall be sick from this cause alone.”

Clearly, Adams was a buyer, not a maker.

Did he party?

Of course, Adams would have attended plenty of social gatherings as a lawyer, ambassador, and a president, but there’s not a lot of information available about his party habits. He may have had an easier time at it if he and Abigail didn’t have to move into a half-finished White House during his only presidential term. In the absence of hard facts, we can take a guess about Adams’s propensity for social cheer. Firstly, all known facts about his drinking habits revolve around him getting up from or going to bed. Not exactly the drinking venue of a party animal.

Most revealing is his personality. John Adams was legendary for being generally disliked by his peers, despite their respect for his contributions to a fledgling nation. One of his closest partners in building the new country was also one of his most bitter rivals: his successor, Thomas Jefferson. His fellow revolutionary and Washington cabinet member, Alexander Hamilton, said he was “petty, mean, erratic, egoistic, eccentric, jealous, and had a mean temper.” However, nobody can say he lacked self-awareness. Adams himself said he was “puffy, vain, [and] conceited.”

That may be a clue as to why his party invites may have gotten “lost in the mail.”

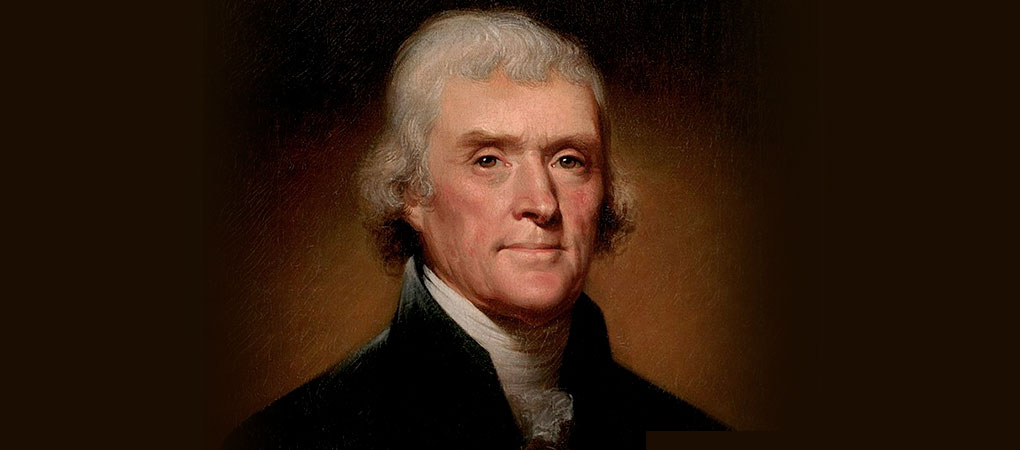

President Thomas Jefferson, served 1801 – 1809

What was his drink of choice?

Almost exclusively wine and, specifically, lighter wines from France and Italy. He wrote extensively about his preferences and admitted that he couldn’t stomach the real strong stuff. As a young man, Jefferson had enjoyed the Madeira and ports that were popular with other colonists.

As he aged and traveled, he left behind such fortified wines, blaming America’s preference for them on the English. He considered his new wines to be better in every way and deeply enjoyed the thrill of tasting them. He wrote, “… in nothing have the habits of the palate more decisive influence than in our relish of wines.”

Was he in the booze business?

Not quite, but he might have kept the entire nation of France in the booze business! Since his first visit to France before serving as Washington’s Secretary of State, Jefferson had been devoted to their wines. He toured vineyards in some of the best regions of the country and, upon his death, his wine cellar at Monticello was almost exclusively stocked with French wines.

That’s not to say that he didn’t “taste around.” He also enjoyed Italian wines and even paid great compliment to a new wine from North Carolina. In fact, he was very invested in the growth of the American wine industry. He tried, in vain, to plant European wine grapes at Monticello, but, to our knowledge, never had a crop worthy of a good enough wine to sell. No matter! He had plenty of connections. During his presidency, he imported thousands of bottles of wine from Europe for both himself and guests.

Did he party?

Given his cultured and somewhat snobbish approach to his beloved wine, it’s not too surprising that President Jefferson drank with utmost responsibility. In a letter to Stephen Cathalan, he precisely described how he viewed his drinking habits: “In the first place, you are not to conclude that I am become a buveur [drinker] My measure is a perfectly sober one of three or four glasses at dinner and not a drop at any other time.” If Thomas Jefferson ever took a sip without being able to properly assess the intricacies of its taste, he would’ve considered it a waste of good wine.